“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

We’ve all heard that mantra more times than we can remember. As with most proverbial sayings, there’s a lot of wisdom behind it.

There is much to be said for sticking with the tried and true. But it’s human nature to tinker. There’s always someone out there trying to fix what isn’t broken.

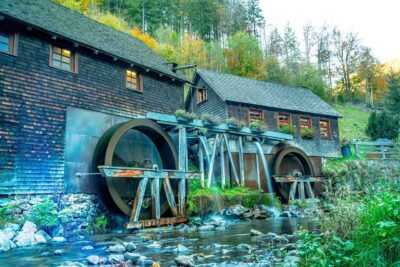

Such is the case in the building materials space. When it comes to choosing what to build with, lumber and wood products have a lot going for them. Wood products are abundant and they come from a renewable resource. They literally grow on trees and thanks to sustainable forestry practices, we can grow all the trees we need.

Relative to other choices, lumber and other wood products aren’t hard to produce. The process is energy-efficient, which means a lower carbon footprint than most competing materials. They’re also easy to use and they perform efficiently and effectively. They get their strength directly from nature and they have a better strength-to-weight ratio than just about any of the alternatives.

What’s truly remarkable about wood products is they represent a big part of the solution to one of the most perplexing issues we face—climate change. As trees grow, they sequester carbon from the atmosphere and store it in their wood. When those trees are harvested and used to make wood products, that sequestered carbon remains stored in those products, usually for decades or even longer. The more we build with wood, the bigger positive impact we can have on climate change. No other readily available building material can claim that sort of benefit.

Wood isn’t perfect, though. It can burn and, if left unprotected and exposed to the elements, it can quickly decay or be destroyed by wood-devouring insects like termites and carpenter ants. We’ve known these things about wood for a long time and we’ve developed effective remedies — pressure treating wood with preservatives or fire retardants — to address these shortcomings.

Can’t stop the tinkerers

Despite wood’s proven track record, competing materials continue to push products designed to fix something that just isn’t broken.

For example, the article, “Taking Your Deck to the Next Level” in the March/April 2024 issue of Deck Specialist magazine, highlights “an array of new choices” for deck framing materials, presenting them as “higher-end” products. Higher-end?? Higher-priced maybe, but likely not higher-end.

The article states steel has “emerged in the last decade as the first real alternative to pressure treated wood for deck framing.” A steel supplier touts sustainability as one of steel’s advantages, but he provides no evidence to support that claim. Maybe that’s because, compared to wood, steel simply cannot legitimately claim superior sustainability.

The piece presents a number of things steel can do, such as carrying the heavy loads from outdoor kitchens and other amenities today’s homeowners like to have on their decks. But it ignores the fact that wood can do those things too.

Another product promoted in the article is “Timber Tech,” a composite product and an aluminum framing product that comes with a 25-year warranty. Guess what? Virtually every pressure-treated preserved wood deck framing product carries a warranty of that length or longer. The article acknowledges that Timber Tech is more costly even than steel, but it also claims it’s “sustainable” on the basis that it’s made with “up to” 50 percent recycled material and is recyclable at the end of life. No mention of the huge energy inputs needed to produce (and, yes, even recycle) aluminum in the first place.

It is interesting, though, that the manufacturer felt the need to make it sound like it’s a wood product.

If it seems too good to be true…

When it comes to achieving code-required fire ratings, the competition is really heating up. Wood is combustible, making it an easy target. Understandably, building codes are strict when it comes to fire. The codes can be confusing, leaving fertile ground for alternative product manufacturers to be evasive in how they present those products.

Fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) isn’t cheap, so there’s no shortage of competing products claiming to be just as good at a lower price point. The FRTW industry has spent decades developing and testing fire-retardant chemical formulations to ensure the products it sells do their job in regard to fire resistance.

In recent years, a number of companies have introduced paints and coatings which they claim can be applied to untreated lumber to achieve the same code compliance as FRTW. These products, they say, offer builders a much less expensive means of gaining code approval for their projects.

Some of these manufacturers, in what seems like an effort to mislead, offer compliance reports referencing non-relevant sections of the building code or they display on their sales literature logos indicating they are members of code-setting organizations, as if such status by itself proves their products are code compliant.

Section 2303.2 of the International Building Code is about as clear as it can be in defining what “fire-retardant-treated wood” is and what it is not. “Fire-retardant-treated wood,” the code reads, “is any wood product that, when impregnated with chemicals by a pressure process or other means during manufacture…” (emphasis added). It goes on to describe the specific test methods that must be used and the results that must be achieved to fit the definition.

Perhaps most importantly, the last sentence of section 2303.2.3 states, “The use of paints, coating, stains or other surface treatments is not an approved method of protection as required by this section.” This sentence underscores, in the eyes of building code officials, the effectiveness of pressure treating fire retardants.

The lower price tags of these alternatives are enticing, and the claims sales reps make sound convincing. But do they work? Do they meet code? Builders who take the chance may find having to tear it all out and start over to satisfy the building inspector is the least of their worries.

Building materials suppliers do a real service to their customers by questioning the need for alternatives when the status quo product ain’t broke and doesn’t need fixing.